03 September, 2019

Corals use sugar from their symbiotic algal partners to control them by recycling nitrogen from their own ammonium waste.

Corals are shown to recycle their own waste ammonium using a surprising source of glucose—a finding that reveals more about the relationship between corals and their symbiotic algae.

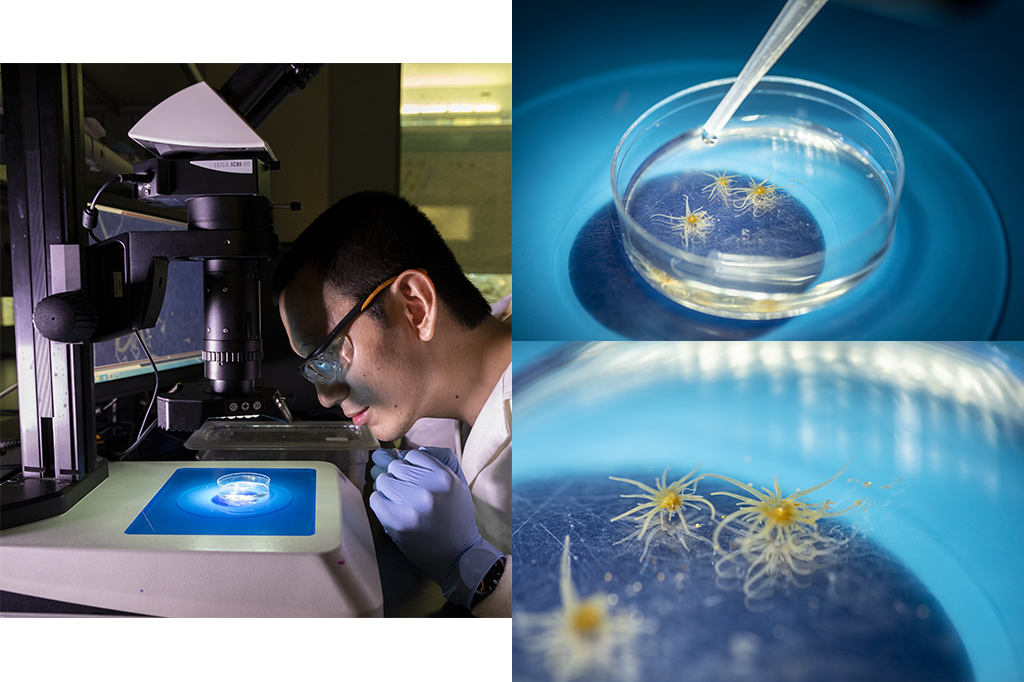

Guoxin Cui looks at the anemone Aiptasia, which is often used as a model for reef-building corals.

© 2019 KAUST

Symbiosis between corals and algae provides the backbone for building coral reefs, particularly in nutrient-poor waters like the Red Sea. Algae and corals cooperate to share nutrient resources, but the precise metabolic interactions at play are still unclear.

Now, KAUST researchers have shown that the coral host uses organic carbon—in glucose sourced from its symbiotic algae—to recycle its own waste ammonium. Previous research had suggested that the algae alone may be responsible for ammonium (nitrogen)

recycling. The KAUST team believes that, by controlling this nitrogen recycling mechanism, the coral host can in turn control algal growth by restricting or enabling nitrogen flow.

“Molecular research on coral-algae symbiosis is relatively

young. The first genetic sequencing study focusing on the coral model anemone Aiptasia was published in 2014,” says

Guoxin Cui at the Red Sea Research Center, who worked on the project under the supervision of

Manuel Aranda. “To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying Aiptasia’s symbiotic relationship with the algae Symbiodiniaceae, we first integrated

all published RNA-sequencing data on this relationship and conducted a meta-analysis.”

Meta-analysis is a statistical method originally developed for medical research, to calculate the precise effects of a specific medicine on patients with a specific disease by combining results from multiple trials.

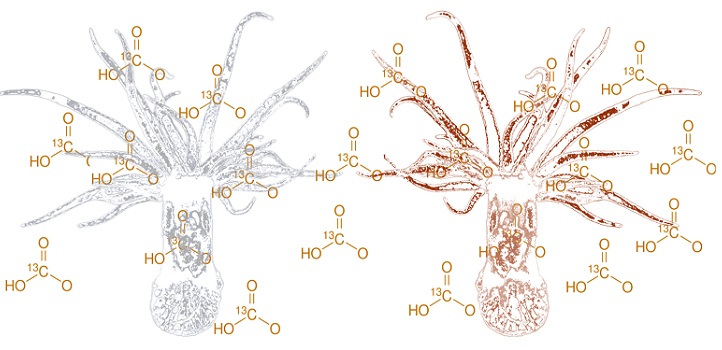

The gray animal (left) is in an aposymbiotic (bleached) state, while the brown animal is the symbiotic state.

© KAUST 2019

“In our case, each gene could be seen as an individual ‘medicine,’ and we can calculate the effect of each gene on symbiosis by monitoring its expression changes across many experiments” says Cui. “Because we use large datasets

compiled from multiple studies, we can be pretty confident of the effect size we calculate for each gene. By focusing on those genes that are definitely associated with symbiosis, we can eliminate noise from unwanted parameters.”

Once the team had identified a set of high-confidence genes, they set up a metabolomics experiment, with the help of their colleagues at KAUST’s Core Labs, using symbiotic and nonsymbiotic (or bleached) Aiptasia. They placed the anemones

in water and added bicarbonate containing labeled carbon-13 (13C) isotopes.

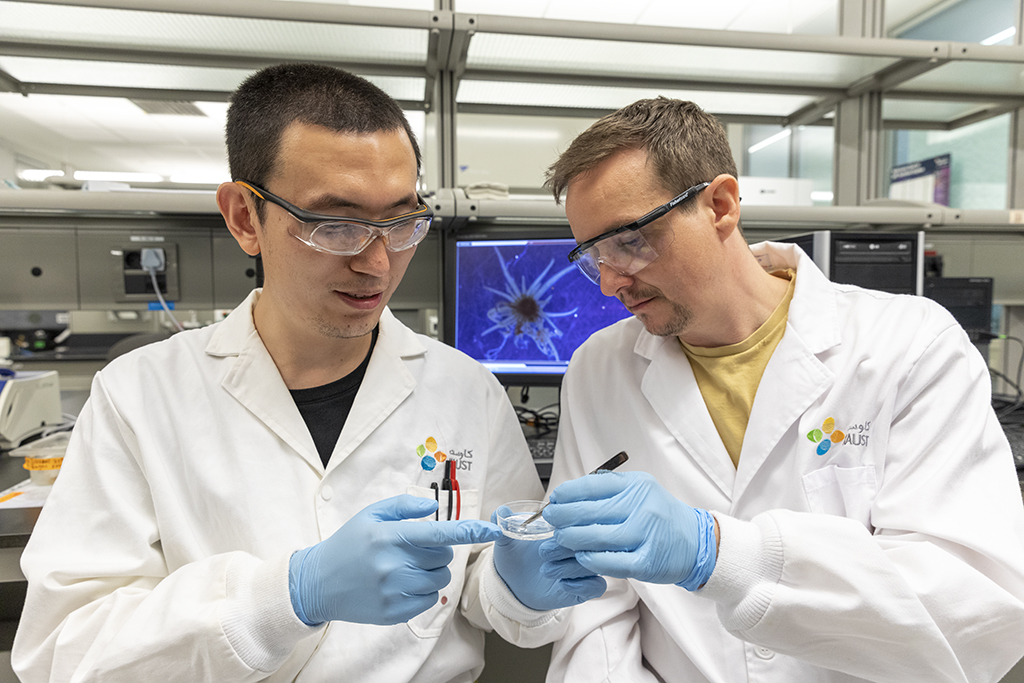

Guixin Cui (left) and Manual Aranda confer over the anemone that is helping them to understand the metabolism of corals.

© 2019 KAUST

The symbiotic algae absorbed the bicarbonate during photosynthesis, transferring the 13C signal to the host’s metabolites. The team could then follow the carbon isotope through the metabolic pathways of the anemones and determine which were

enriched with 13C.

“Our results show that competition for nitrogen is a key mechanism within coral-algae symbiosis,” says Cui. “These insights will help us understand what goes wrong when the relationship is placed under stress, for example, because of shifting climates.”