26 March, 2020

-By David Murphy, KAUST News

Recent increases in global water temperatures are causing a progressively detrimental effect on marine life and ecosystems in our oceans. Human activities generating excess greenhouse gas emissions have resulted in an increase in the average sea surface temperature of approximately 0.13 C per decade over the past 100 years, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

.jpg?sfvrsn=5de68d01_2)

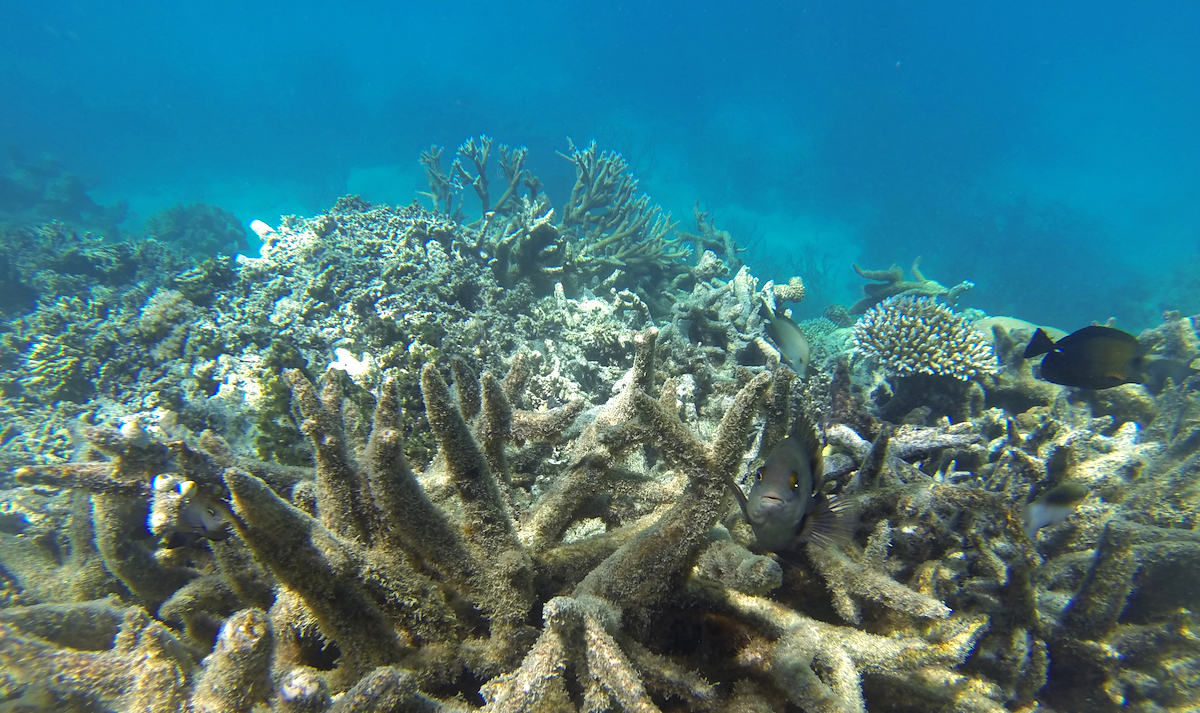

Ocean warming can lead to multiple harmful environmental knock-on effects, including higher sea/ocean levels, greater extreme weather events, a spread of invasive species and diseases, threats to global food security and a loss of breeding grounds for marine animals. Warmer water temperatures also trigger coral bleaching, a phenomenon that affects almost every tropical and subtropical body of water in the world. Coral subjected to higher than average water temperatures expel the algae (zooxanthellae) living in their tissues, causing the coral to turn completely white, or to "bleach."

KAUST Red Sea Research Center (RSRC) scientists, including Manuel Aranda, associate professor of marine science, and Christian Voolstra, adjunct associate professor of marine science, generated data that suggest areas of the Red Sea harbor reef-building corals that live well below their thermal bleaching thresholds. In particular, the northern part of the Red Sea stands out as a thermal refuge of global importance.

"Typically, in every area, bleaching is usually observed at only +1 to 2 C above the mean summer max temperature," explained Voolstra. "In the northern Red Sea, it is +5 C above mean summer max."

"It seems that Northern Red Sea reefs constitute a global coral reef refuge that deserves our attention and protection," he continued. "The Northern Red Sea is the only place on Earth that I am aware of with this characteristic. These coral reefs have a climate change insurance for the next 100 years. We should make sure that this resource is conserved, and we should also invest in the research to figure out why this is the case."

Understanding how bleaching affects corals in different areas of the Red Sea and how to best decode these findings is important to both researchers.

"Corals in the Red Sea are bleaching—at least in the south where the temperature is higher. From a local perspective, we would like to understand how we can help Red Sea corals to [become] even more thermotolerant," Aranda noted. "For us, this research is super interesting because it might allow us to understand how corals can adapt to future climate change scenarios."

"In the Red Sea, in the summertime, the average water temperature is above 32 C, and this would kill—basically wipe out—corals in the Caribbean, in the Great Barrier Reef, etc.," he continued. "However, corals here can survive these temperatures, and we're very much interested in finding out why—and of course how—so we can use this knowledge to help corals elsewhere."

.jpg?sfvrsn=74db8881_2)

In 2015, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared the existence of the third global coral bleaching event on record, which affected corals in the Red Sea. Coral reefs in the Southern Red Sea were considerably more affected than reefs in the northern part.

"Why does the Northern Red Sea not experience mass bleaching events as much as the Central and Southern parts of the Red Sea?" Voolstra asked. "We don't really know yet for sure. Several theories have yet to be conclusively proven."

"One theory is that around 15,000 years ago, the Red Sea was disconnected and dried out," he explained. "In the following recolonization period, all corals had to pass the warmer southern waters, which is why we see corals in the Northern Red Sea that have much higher thermotolerance than expected."

"Another theory is that higher salinity contributes to increased thermotolerance via osmoadaptation. Curiously, the Northern Red Sea is colder but features a higher salinity. Typically warmer temperatures go hand in hand with higher salinities due to increased evaporation," Voolstra added.

To understand why the Northern Red Sea harbors so many resilient and temperature-resistant corals, scientists have to compare the genomic underpinnings of Northern Red Sea corals to Central and Southern Red Sea corals. The resilient corals may serve as a base to help reduce the ecological impact of coral bleaching worldwide.

"KAUST and Saudi Arabia are pretty much the only places where you have access to Red Sea corals across their entire north-south gradient," Voolstra noted. "This means we can study resilience across substantial environmental differences in a comparative framework. We are currently conducting a large-scale study to pinpoint the genomic differences between Northern and Southern Red Sea corals."

"We're looking at this using different techniques and different methods—mostly based on what we call genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics—and bolstering this with physiological evaluation," Aranda said. "We...look at the raw data but then actually measure in the organisms what is really happening. We try to combine these old-school physiological techniques with all the new -omics methods to give us an inkling of what could be going on."

The research carried out by Aranda, Voolstra and their RSRC colleagues has not been done in this form and to this extent before in the Red Sea. In fact, most of the RSRC-driven epigenomics research of the sea has not been done before at all.

"This research is not only something novel for the Red Sea, but this is also something novel globally [and] in general," Aranda emphasized.

Both researchers believe that, through increasing the public's understanding of coral biology, corals' unique symbiotic relationship with algae and their response to environmental stress, etc., the RSRC will help inform future development of Saudi Arabia's coastal regions and the entire Gulf region.

"People in Saudi Arabia and all over the world are becoming aware that coral reefs are threatened," Voolstra said. "The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change adopted very clear language to that extent: We need to act in the coming 20 years to save as many reefs as possible until we have developed or engineered broader solutions to counter the effects of a changing climate."

"Saudi Arabia has some of the most pristine reefs in the region," he continued. "By the size of the coral reefs in its waters, it is a main player and can become a leader in our efforts to preserve this unique local and global resource."

Aranda and Voolstra are unsure whether the damage caused by coral bleaching can ever be truly reversed. Some coral and marine life in affected regions will continue to survive regardless—albeit in environments that are diminished and less vibrant or diverse than before, the researchers noted. It is humanity's job to protect corals and reefs from some of the most irresponsible human-made aspects of global climate change, they stated.

"As to the reversibility—that's a hard question to answer," Voolstra said. "In principle, bleaching is reversible, but we need to make sure that conditions are met that allow coral to recover. This includes reducing local impacts, such as overfishing, sewage outlets, and sedimentation, all of which have been shown to negatively affect resilience and recovery."

"Once the coral is dead, these reef structures will be lost, and with the loss of the structure, all associated species lose their habitat," Aranda added. "What you have is a very barren 'seascape' that is mostly dominated by algae. Sure, there will be some species that will be able to feed on the algae, but compared to the biodiversity [that was there] before, [this] will be much, much smaller and incapable of supporting the life and biodiversity that we enjoy at present in our oceans and seas."